Every website redesign starts the same way. Someone opens design software too early. Stakeholders start requesting features. The team debates colors and fonts while nobody has documented how visitors become customers.

Then the beautiful design launches and doesn’t convert.

The missing step isn’t another mood board or stakeholder meeting. It’s a storyboard. But not the kind you learned about in design school.

A user journey storyboard maps how different visitors become customers. Not how pages connect. Not where the logo goes. How real people with real questions move from curiosity to action.

If you’re a Marketing Director or CEO planning a redesign, you don’t need more layouts. You need clarity on how your best buyers move through your site.

Most teams skip this because it feels like a detour when everyone’s excited to start designing. The storyboard isn’t visual enough to feel like progress. You can’t show it to clients and get that “wow” reaction.

So teams jump straight to wireframes, mockups, and typography choices. Every design decision becomes a debate about personal preference instead of a strategic conversation grounded in how your customers think.

The difference between storyboards and everything else

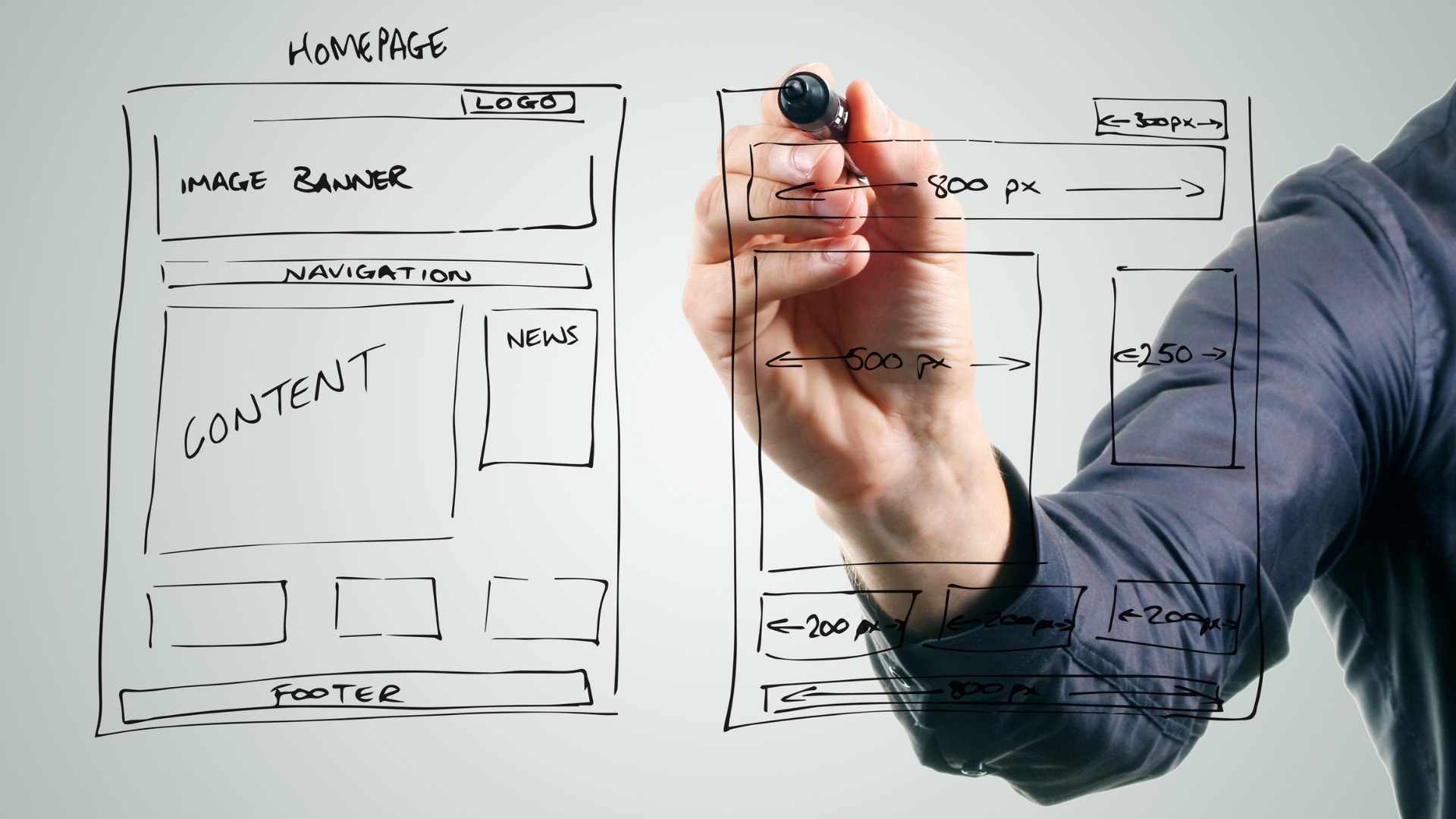

Three tools get confused constantly: sitemaps, wireframes, and storyboards. They do different things.

A sitemap shows how pages connect. Homepage links to Services, Services links to individual offerings, those link to Contact. It’s organizational architecture. Essential, but it doesn’t tell you anything about experience.

A wireframe shows what goes on a page. Hero section here, testimonials there, call-to-action in the bottom third. It’s structural layout. Also essential. Still doesn’t tell you about experience.

A storyboard shows the narrative. What questions does someone have when they land? What objections emerge as they explore? What sequence of information converts curiosity into action? It maps the story visitors experience, not just the boxes they scroll past.

Think of it this way: a sitemap is the org chart, a wireframe is the floor plan, and a storyboard is the tour guide’s script.

What a website storyboard actually looks like

You can sketch this as panels with arrows, annotations, and rough layouts if that helps you think. Many teams use whiteboards or digital tools to visualize the flow.

But the visual format isn’t the point. What matters is that each panel reflects real user behavior and decisions, not someone’s guess about what “feels right.”

A useful storyboard typically includes panels representing the visitor’s state of mind at each stage, with arrows showing the logic that moves them forward. Annotations capture friction points and questions. Low-fidelity sketches suggest content types without locking in layout.

The panels don’t need to be beautiful. They need to be accurate.

This is the storyboard web design work that should happen before anyone opens Figma or starts arguing about button colors.

The research problem nobody talks about

Here’s where most storyboarding advice falls apart. It treats the storyboard as a standalone design exercise. Grab some sticky notes, sketch some panels, sequence your pages. Done.

That approach produces organized guessing.

A useful storyboard comes from somewhere. It’s the output of research, not a replacement for it. The panels might look professional without that foundation, but they’re still assumptions about what visitors want to see and in what order.

Where does that research come from? Stakeholder interviews reveal internal assumptions and business priorities. Customer research shows how real buyers think and what questions they have. Competitive analysis maps what visitors have already seen before landing on your site.

Without that foundation, storyboarding is just a creative exercise. With it, the storyboard becomes a documented plan every design decision can be measured against.

The question isn’t “should we storyboard?” It’s “do we know enough about our visitors to storyboard effectively?”

Why different visitors need different journeys

Generic user personas create generic storyboards. “Our user is a professional who wants to solve their problem” tells you nothing useful about how to sequence information.

Someone who searched “website redesign cost” has different questions than someone who clicked through from a LinkedIn post about brand strategy. Someone referred by a trusted colleague starts with different assumptions than someone comparing five agencies in browser tabs.

Entry context matters: where did they come from, and what expectations does that create?

Knowledge level matters: are they sophisticated buyers who’ve been through this before, or first-timers who need foundational education?

Urgency matters: are they actively evaluating this quarter, or researching for a project that might happen someday?

One storyboard rarely serves all these visitors well. Identify your two or three primary visitor types and map distinct journeys for each. Then evaluate which pages serve multiple journeys versus which need to fork based on visitor type.

The five things a useful storyboard captures

Every panel in your storyboard should answer questions about the visitor’s experience at that moment in their journey.

Where are they in the decision process? Just discovered you exist? Comparing you against alternatives? Ready to reach out but need final reassurance? The same content lands differently depending on where someone is mentally.

What questions do they have right now? Not what you want to tell them. What they’re actually wondering. At early stages, it’s “what do you actually do?” Later, it’s “can you handle my specific situation?” Even later, it’s “what happens if I reach out?”

What objections are surfacing? Every step of the journey creates potential hesitation. Too expensive. Not specialized enough. Seems complicated. Unknown reputation. The storyboard maps where these objections typically emerge and how each panel addresses them.

What proof do they need? Claims without evidence don’t convert sophisticated buyers. Where in the journey do they need case studies? Testimonials? Process documentation? Mapping this prevents front-loading proof before visitors even understand what you do.

What’s the next logical step? Each panel should have a clear answer for “and then what?” Sometimes it’s scrolling to the next section. Sometimes it’s navigating to a different page. Sometimes it’s reaching out. The storyboard makes this explicit so every page has intentional momentum.

User journey storyboards in practice

Theory only goes so far. Here’s what user journey storyboarding actually looks like for three types of B2B companies.

Healthcare technology company

The visitor is a Director of Operations at a regional hospital system. She’s evaluating patient engagement platforms after their current vendor’s contract renewal came in 40% higher than expected.

Entry context: She searched “patient engagement platform comparison” and clicked through from a listicle that mentioned this company. She’s already seen three competitor websites today. She’s skeptical because every platform promises “improved outcomes” without explaining how.

Stage 1: Orientation

First question: “What specifically does this platform do?” She’s seen too many healthtech companies hide behind vague language. She needs concrete functionality in the first ten seconds or she’s bouncing to the next tab.

Storyboard note: Homepage hero must state specific capabilities, not just “patient engagement solutions.” Within scroll depth one, she should understand the core function.

Stage 2: Relevance check

She’s scanning for signals that this company understands hospital operations specifically. Does this platform work for organizations her size? Have they dealt with Epic integration challenges? Do they understand the compliance requirements she’ll have to navigate internally?

Storyboard note: Social proof needs to appear early, filtered for relevance. Testimonials from similar-sized health systems. Integration logos that match her tech stack. Compliance certifications visible without hunting.

Stage 3: Differentiation

She’s thinking about the three other tabs open in her browser. What makes this option different? Not better in some abstract sense. Different in ways that matter for her specific evaluation criteria.

Storyboard note: Competitive differentiation can’t be buried on an “About” page. It needs to surface before she’s mentally checked out.

Stage 4: Validation

She’s becoming interested but needs ammunition. She’ll have to justify this recommendation to her CFO and CMO. What evidence can she bring to that conversation?

Storyboard note: Case studies need to provide borrowable proof. Statistics she can quote. Timelines she can reference. Outcomes she can project onto her own organization.

Stage 5: Risk assessment

Before she reaches out, she’s evaluating what could go wrong. What does implementation actually involve? What internal resources will this require? She’s not ready to talk to sales until she’s confident this won’t become a career-limiting recommendation.

Storyboard note: Process transparency and “what to expect” content addresses objections she won’t voice on a sales call. Pricing transparency prevents sticker shock that derails conversations later.

Conversion trigger: She reaches out when she has enough information to frame this as a credible option worth her organization’s time to evaluate formally. The website’s job isn’t to close the deal. It’s to make her confident enough to start a conversation.

Professional services firm

The visitor is the CEO of a 45-person manufacturing company. His longtime corporate attorney just retired, and he needs to find a new firm for an upcoming acquisition. A colleague mentioned this firm at a conference last month.

Entry context: He typed the firm name directly into Google after digging up the recommendation from his notes. He’s not comparison shopping yet. He’s validating whether this referral is worth pursuing. He’ll give the website about 90 seconds before deciding whether to call or keep looking.

Stage 1: Credibility check

First question: “Are these people serious?” He’s evaluating professional polish, but more importantly, he’s looking for signals of expertise in transactions like his. He doesn’t need a generalist.

Storyboard note: Professional services buyers from referrals have different entry points than searchers. They’re validating a recommendation, not discovering options. The homepage needs to confirm credibility fast, then get out of the way.

Stage 2: Expertise verification

He’s looking for evidence of M&A experience specifically. Attorney bios, case descriptions, practice area content. Have they handled deals in his revenue range? His industry? His deal structure?

Storyboard note: Practice area pages do heavy lifting for referred traffic. They need to answer “have you done this specific thing?” not just “do you offer this service category?”

Stage 3: People evaluation

He’s going to work with actual humans, not a firm name. Who would handle his deal? What’s their background?

Storyboard note: Attorney bios matter more than firms often realize. For referred traffic evaluating a specific engagement, the “who” often matters more than the “what.”

Stage 4: Process sanity check

He’s wondering what this would actually involve. He’s been through acquisitions before and knows they’re complex. Is this firm going to make his life easier or create more work?

Storyboard note: Process content for professional services reduces friction for sophisticated buyers. They’re not looking for education. They’re looking for evidence of competence and compatibility.

Conversion trigger: He picks up the phone when the website confirms his colleague’s recommendation was credible and he’s seen enough relevant experience to justify a conversation. The bar is lower than cold traffic because trust transferred from the referral. The website’s job is to not screw that up.

B2B software company

The visitor is a Marketing Director at a mid-sized SaaS company. She’s researching marketing automation platforms because their current tool can’t handle the segmentation complexity their growth requires. She’s three months from contract renewal and building a business case for switching.

Entry context: She searched “marketing automation for SaaS” and clicked through from an organic result. She’s used three different platforms across her career and is cynical about feature claims. She’s looking for a platform that can grow with them through their Series B and beyond.

Stage 1: Capability verification

She’s scanning for specific features, not marketing language. Can it handle behavioral triggers across multiple product lines? Does it integrate with Salesforce the way she needs? She’s not going to read paragraphs of copy. She’s going to scan for capability keywords and integration logos.

Storyboard note: Sophisticated software buyers skim. Information architecture matters more than persuasive copy. Feature comparison and integration documentation should be findable within seconds.

Stage 2: Scalability assessment

She’s thinking eighteen months ahead. They’re at 50 employees now, probably 150 by the time this contract would renew. Will this platform grow with them or become another migration headache?

Storyboard note: Growth-stage buyers evaluate future state, not just current needs. Content needs to address “what happens when we get bigger.”

Stage 3: Social proof filtering

She wants to see companies like hers. Similar size, similar stage, similar complexity. Customer logos from enterprise companies don’t impress her. They make her wonder if this platform is overkill.

Storyboard note: The most relevant proof isn’t always the most impressive names. Let visitors find evidence from companies that match their situation.

Stage 4: Total cost analysis

She’s building a business case. She needs to understand not just licensing costs but implementation timeline, internal resource requirements, and migration complexity. She’s been burned by platforms that seemed affordable until the hidden costs emerged.

Storyboard note: Pricing transparency helps sophisticated buyers more than it hurts conversion. She’s going to find out eventually. Making her work for it just frustrates her.

Stage 5: Internal selling preparation

Before she reaches out, she’s gathering materials to justify this evaluation to her CEO. She needs documentation she can forward. Comparison frameworks she can present. ROI calculators she can adapt.

Storyboard note: B2B software decisions involve multiple stakeholders. Content that helps your champion sell internally accelerates deals more than content that only speaks to the primary evaluator.

Conversion trigger: She requests a demo when she’s confident this platform is worth her team’s time to evaluate formally and she has enough material to justify that time investment to her boss. The website’s job is to arm her for the internal conversation that happens before any sales conversation.

Each example shows the same pattern: specific questions at specific stages, and a website that either answers them or loses the opportunity.

Documenting these journeys does more than guide design. It changes how teams make decisions.

How storyboarding turns opinion debates into strategic decisions

Without a documented plan, every stakeholder fills gaps with their own assumptions.

Sales wants lead capture forms everywhere. Marketing wants social proof scattered throughout. The CEO keeps sending competitor websites asking “why can’t ours look like this?” Customer service wants FAQs prominent in main navigation.

All these requests seem equally valid when there’s no documented plan. Teams try to accommodate everyone. The result is a website that attempts everything and accomplishes nothing.

A storyboard changes those conversations.

When someone requests a change, you can evaluate it against the documented journey. Does this serve visitors at this stage? Does it advance them toward the next logical step? Does it address an objection we’ve identified, or does it interrupt a journey that’s working?

Some requests will improve the storyboard. Many won’t. The difference is you now have criteria for evaluation beyond “that seems like a good idea” or “the CEO asked for it.”

“Should pricing be above or below features?” becomes a question about visitor psychology at that journey stage, not a debate about visual hierarchy preferences.

“What should the homepage say?” becomes a question about what different visitor types need to understand first, not a creative exercise in clever copywriting.

“Do we need a separate page for this?” becomes a question about whether that content serves a distinct journey stage or interrupts existing flow.

This is what strategic alignment looks like. Not everyone agreeing, but everyone evaluating against the same documented criteria.

What this actually takes

Storyboarding adds time to the planning phase. Expect roughly 5-15 hours of work, depending on project complexity and how many distinct visitor types you’re mapping.

That investment compounds. A few extra hours of planning consistently saves entire rounds of design revisions later. When every design decision traces back to documented visitor journeys, there’s less back-and-forth about whether something “works.” You can evaluate it against specific criteria.

The alternative is launching and then spending months figuring out why the beautiful design doesn’t convert. Most websites go through this. They redesign based on what looks modern, launch, watch metrics disappoint, and then start the optimization grind to fix what should have been planned from the start.

The research foundation matters more than the storyboard format. Some teams use detailed panels with sketches and annotations. Others use simple documents mapping journey stages to content requirements. The format is flexible. The thinking is not.

If you’re working with an agency, ask what research informs their recommendations. If they can’t point to specific customer insights, competitive analysis, or stakeholder interview findings, they’re guessing. Confident guessing, maybe. Still guessing.

When simpler approaches work fine

Not every website needs elaborate user journey storyboarding.

If your site has one audience and one primary action, a clear conversion flow can be enough. Single-audience sites don’t require this level of complexity.

The approach outlined here is designed for sites serving multiple distinct audiences with different entry points and conversion paths. B2B companies with varied buyer personas. Service businesses with different service lines attracting different customer types. Organizations where visitors arrive from multiple channels with multiple intents.

If that’s your situation, the upfront investment in mapping these journeys pays off across every design decision that follows.

The goal isn’t maximum process. It’s appropriate process for your situation.

Putting this into practice

Start with research, not panels. What do you know about how your visitors think, what they’re looking for, and what objections they carry? If the answer is “not much,” start there before sketching anything.

Identify your primary visitor types. Not demographic segments. Behavioral segments. Who arrives from search versus referrals? Who’s actively buying versus researching for later? Who’s sophisticated versus new to this? Map two or three distinct types at most.

For each visitor type, document the journey. What do they need to understand first? What questions emerge as they learn more? What proof builds confidence? What’s the logical path from landing to conversion?

Evaluate your current site against these journeys. Where does it serve them well? Where does it interrupt or confuse? Where are there gaps between what visitors need and what pages provide?

Use this analysis to inform design decisions. Every structural choice, every content decision, every page that gets created or removed should trace back to how it serves documented visitor journeys.

Then track what happens. After launch, analytics show whether visitors follow the journeys you mapped. When they don’t, you have specific hypotheses about why and what to test.

The storyboard isn’t a one-time document that sits on a shelf after launch. It’s a working reference that evolves as you learn more about how visitors behave.

Need help mapping user journeys for your next website project? Let’s talk.